By Kai Weiss and Simon Sarevski

By Kai Weiss and Simon Sarevski

While these laudable goals may be part of the decision, IKEA most likely decided to pursue the new policy for the simple reason that it wants to achieve solid revenue. “Corporate social responsibility,” one of the favorite buzzterms of today’s business world, was not necessarily the reason. A much more likely explanation is that IKEA’s profits fell by a third last year, and it had to cut 7,500 jobs. Caring for the environment is “hip” or “woke” these days, so the Swedes seem to think it could be profitable for them to invest in such endeavors.

Market Environmentalism

Nonetheless, IKEA’s new rental program is a great example of how the market can protect the environment after all. This is something that seems contradictory to most people today, and when the Property and Environment Research Center’s (PERC’s) Terry Anderson coined the term “free-market environmentalism” a few decades ago, it was described by many as nothing more than an oxymoron.

Nonetheless, the hundreds of intergovernmental treaties that governments have signed over the last decades to fight global warming had a rather minuscule effect and resembled more nonsensical feel-good declarations or demands for more global financial redistribution. Environmental policies by national governments have led, if anything, to skyrocketing electricity prices, and politicians flying across the world to discuss climate change at conferences has certainly not decreased the carbon footprint, either.

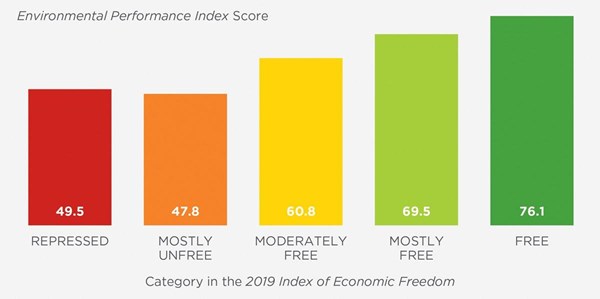

Markets have. The just-released 2019 version of the Heritage Foundation’s Index of Economic Freedom shows that when comparing it with the Environmental Performance Index (EPI), the freer an economy is—i.e., the less government interferes in an economy—the better it protects the environment. The EPI looks at 24 indicators from air pollution, water quality, biodiversity, and fisheries to CO2 emissions. Those countries Heritage considers economically free boast an EPI score of 76.1 points (of 100), while those countries that are economically repressed score only 49.5.

More Freedom Means More Concern for the Environment

This is not particularly surprising. As the Heritage index also establishes, the freer an economy is the more prosperous the population. And only a prosperous population, such as ours in the West, would give much thought to how it could become more environmentally aware. It is only in such societies that IKEA would ever think it could be profitable to appear to care for the environment. In poorer and repressed societies where life is about survival, it is of the utmost importance to, well, survive, instead of lowering one’s carbon footprint or debate whether the Grand Canyon or the Indiana Dunes should be national parks for recreational activities.

Even more so, in societies that are economically free, voluntary exchanges and interactions through property rights (i.e. the cornerstones of a market economy) will dominate. A private property regime provides the incentives for property owners to take care of the property responsibly. As PERC’s Holly Fretwell notes:

When we have private property, we tend to have better incentives to take care of things and be good stewards. This is because we as the individuals who own property are the ones who will benefit from taking good care of it – and if we don’t take good care of our property, then we are the ones who are burdened by lower value to that property.

Property owners will also have to respond to signals from other market participants—if the others want the environment protected, it would be quite detrimental for property owners to not do so, too, since it could possibly be seen as a social vice to destroy the environment.

But also, in a free economy, one has the opportunity to protect the environment by having the possibility to be innovative, to adapt to circumstances, to dare to invest one’s resources to make the world—or, if one is a little more prudent, your close surroundings—a better place. There are countless examples of how private individuals and companies, through entrepreneurial endeavors, are trying to protect the environment, from the ownership rights of rhinos in Africa to projects like the American Prairie Reserve, which buys land from private owners to create a habitat for wildlife in eastern Montana.

The Consequences of Government-Sponsored Environmental Protection

This is in stark contrast to government-enforced environmental programs, like national parks, which, regardless of whether they are a good idea or not, are subject to government shutdowns each year. They are often trashed or closed during those shutdowns. It is also in stark contrast to repressive economies, perhaps the most shocking of which is the Soviet Union, which, as Richard Stroup reckons, could be one reason why interest in environmental protection has increased in recent decades after the fall of the Communist mega-state:

The failures of centralized government control in Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union awakened further interest in free-market environmentalism in the early 1990s. As glasnost lifted the veil of secrecy, press reports identified large areas where brown haze hung in the air, people’s eyes routinely burned from chemical fumes, and drivers had to use headlights in the middle of the day. In 1990 the Wall Street Journal quoted a claim by Hungarian doctors that 10 percent of the deaths in Hungary might be directly related to pollution. The New York Times reported that parts of the town of Merseburg, East Germany, were “permanently covered by a white chemical dust, and a sour smell fills people’s nostrils.”

Whether IKEA will succeed in its endeavors to look (or even better, be) more environmentally friendly is yet to be seen. But what is clear is that in an age where climate change is seen as one of our biggest challenges and when people want to spend ever-more time outdoors to enjoy the natural beauty that is scattered all across the US and the world, it is market solutions that provide the incentives and opportunities for entrepreneurs, innovators, and, indeed, regular individuals, to protect the environment.

Kai Weiss is a Research Fellow at the Austrian Economics Center and a board member of the Hayek Institute.

Simon Sarevski is a spring intern at the Austrian Economics Center. He holds a bachelor’s degree in financial management from Ss. Cyril and Methodius and is involved with European Students for Liberty.

Image credit: Pixabay

This article was sourced from FEE.org