March 19, 2015

By Craig McKee

To believe the official story of 9/11 you have to swallow an awful lot. You have to believe the laws of physics can be suspended for a day, that planes can disappear after crashing, and that Muslims accused of being suicide hijackers can still be alive after the deed is done.

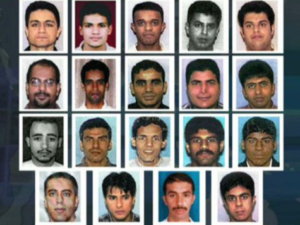

About that last one. Essential to the deception was the premise that 19 Muslim extremists hijacked four domestic flights on the morning of September 11, 2001 with the intention of flying them into predetermined targets.

But do we really know who these alleged hijackers were? Do we know they carried out any hijackings? Do we know they were even at the scenes of the crimes? In fact, as researcher Elias Davidsson demonstrates in his recent book Hijacking America’s Mind on 9/11: Counterfeiting Evidence, there is not one shred of authenticated evidence that any of the 19 men blamed for the “attacks” ever boarded any planes. And even if there were, this would not prove they participated in any hijackings.

Davidsson shows that evidence proving that the guilt of the accused hijackers simply does not exist. Beyond that, the names on the official list have changed multiple times with no adequate explanation for why or how. Several accused even turned out to be alive after 9/11, a fact that is not mentioned in the 9/11 Commission Report even though it was known long before the report was written. The North American media have also ignored this critical fact.

In his analysis, Davidsson lists five ways that guilt could have been proven but was not (we get into details a bit later):

- Authenticated passenger lists or flight manifests that feature the names of the alleged hijackers;

- Authenticated boarding passes showing that they boarded the planes;

- Sworn testimonies of anyone who witnessed any of the accused boarding;

- Authenticated security videos showing them boarding the planes and;

- Physical remains with chain of custody reports.

Davidsson contends that not only has the government not proven its case against the 19, it has not even established probable cause.

Researcher Jay Kolar, in his article “What We Now Know About the Alleged Hijackers,” published in The Hidden History of 9-11 (edited by Paul Zarembka), points out that then FBI director Robert Mueller has admitted that the case against the “hijackers” would never stand up in a court of law.[1] This, however, does not stop the FBI and the mainstream media from calling them mass murderers. Mueller was also quoted in the Los Angeles Times on Sept. 21, 2001 as saying there is considerable doubt about the identities of the alleged perpetrators.

No proof these men hijacked anything.

“We have several hijackers whose identities were those of the names on the manifests,” Mueller said. “We have several others that are still in question. The investigation is ongoing, and I am not certain as to several of the others.”

Kolar writes that all the evidence used to support the allegations – including videos, photographs, in-flight phone calls, and cockpit audio tapes, “have been proven to lack authentication if not also proven, with corroboration from other evidence, to be fabrications or forgeries.”[2]

And the investigation Mueller mentioned didn’t last long. President George W. Bush called it off one month after it began with the excuse that the manpower was needed to investigate the anthrax attacks. Of course these turned out to be another false flag, directly linked to the 9/11 deception (see Graeme MacQueen’s book The 2001 Anthrax Deception: The Case for a Domestic Conspiracy).

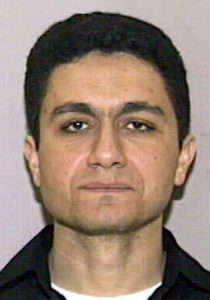

David Ray Griffin also points out in The 9/11 Commission Report: Omissions and Distortions that there are other key pieces of information that were available long before the release of The 9/11 Commission Report in 2004 that contradict the official hijackers scenario. One was that multiple media reports had made it clear that Mohamed Atta (allegedly the pilot of Flight 11) drank, used cocaine, received lap dances, and used prostitutes – and he was not the “fanatically” devout Muslim the Report claims. Another was that Hani Hanjour (the alleged pilot of Flight 77) was so poor a pilot that he had been refused rental of a two-seater Cessna just a month before 9/11. This contradicted the Report’s claim that Hanjour was the operation’s most experienced pilot.

The elements of proof

Here is a more detailed look at the five types of evidence that Davidsson asserts might have proven the guilt of the 19 men accused of this momentous crime:

Authenticated passenger lists or flight manifests: Under normal circumstances it would be a simple thing to prove whether someone was on a particular flight or not. The official flight manifests are legal documents that are used to establish the identities of passengers when, for example, insurance claims are being made.

Davidsson requested these official manifests from American Airlines in 2004, but the request was denied. An airline spokesperson stated that the official lists had been turned over to the FBI and that they had in turn released a list of names to the media, adding that the airline “is not in a position to release further information or to republish what the government agencies provided to the media.”[3] He made another attempt in 2005 and was given a list of 53 passengers with the names of the alleged hijackers redacted. When he approached United Airlines, he was told to contact the FBI.

Davidsson made a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request to the FBI for the original passenger manifests and was told that the lists were available on the Internet and at the U.S. Department of Justice web site. But all that was available at the site were seating arrangements, not a passenger list.

Perhaps the biggest problem with the passenger lists that have been released is that the identities of several of the alleged hijackers have changed with no explanation. We also know that several of the people on the FBI’s list were still alive after 9/11 and could not have been part of any possible hijackings. Some names were deleted and others substituted, but even some of the new names belonged to people who turned out to be alive. Kolar reports that at least 10 of the current list of 19 were still alive after 9/11.[4]

In his book, Davidsson points out that former Drug Enforcement Agency administrator and former Commissioner of U.S. Customs and Border Protection, Robert Bonner, testified before the 9/11 Commission that he had been handed a sheet containing the names of the 19 probable hijackers by 11 a.m. on 9/11. The problem is that this is well before the U.S. military had even confirmed which planes had been hijacked. Where did he get this list?

In 2012, Davidsson made another FOIA request to the FBI asking for “flight manifests for hijacked flights.” This was denied even though the names of the hijackers and the passengers had been publicly known for years. He concludes from his research that either the FBI does not possess the original flight manifests or those lists do not reflect the current list of alleged hijackers.

No authenticated boarding passes: As Davidsson reports, in 2001 American Airlines issued boarding passes with stubs to be torn off by airline employees. But no boarding pass stubs have been produced for any of the alleged hijackers that boarded either of the AA flights (11 and 77). The 9/11 Commission says it received “copies of electronic boarding passes for Flight 93.”

As Davidsson reports, there is one story recounted in Tom Murphy’s book Regaining the Sky that appears nowhere else: Terry Rizzuto, the United Airlines station manager at Newark Airport (where Flight 93 left from), had just finished arranging to release to the FBI the manifest and the Passenger Name Record from Flight 93. She headed to the gate that the plane had left from to speak with staff, and when she arrived, she was handed four boarding passes by an unnamed supervisor, who tells her that they are for the four alleged hijackers of the flight.

When she asked how they found this out so fast, the supervisor replied: “They were too well dressed. Too well dressed for that early in the morning. And their muscles rippled below their suits. Yes, and their eyes.”

No witnesses to boarding: There are simply no witnesses who can state that any hijackers actually boarded any planes. No ticket takers, no security personnel, no one. In fact, there is no one who makes a credible claim to have seen any of them at boarding gates or security checkpoints either – even though the 9/11 Commission Report states (p.451) that 10 of the 19 were selected by an automated system for additional security screening. And the collection of knives and box cutters that they allegedly used to take over the planes were somehow not detected either by electronic screening or through individual searches.

There were a couple of instances where airport staff did say they believe they saw one or more of the accused hijackers, but these did not stand up because of serious factual contradictions. These included wrong physical descriptions, incorrect descriptions of the types of clothes the men were wearing or whether they wore glasses, and in one case an airport employee said he believed he recognized one of the men from a photo who he said boarded one of the American Airlines planes. The problem was that this “hijacker” is supposed to have flown on one of the two United Airlines flights.

No authenticated security video: Had 19 hijackers boarded four planes, they should each have been caught on camera dozens of times as they moved through the terminals. Instead, there are only two videos that show any alleged hijackers at any airports on 9/11. These are examined by the 9/11 Consensus Panel in their “Point Video-1: The Alleged Security Videos of Mohamed Atta during a Mysterious Trip to Portland, Maine, September 10-11, 2001” and “Point Video-2: Was the Airport Video of the Alleged AA 77 Hijackers Authentic?”

One video allegedly shows Mohamed Atta and Abdulaziz al-Omari going through security at the airport in Portland, Maine early on the morning of Sept. 11. This video was released to the press soon after 9/11. Atta and al-Omari were purported to have rented a car and driven from Boston to Portland on Sept. 10. They allegedly appeared on security video at a gas station and a Walmart that day.

In the case of Portland Airport video, not one but two times were stamped on the images – 5:45 a.m. and 5:53 a.m. The latter time is just seven minutes before the plane’s scheduled take-off. The trip itself makes no sense given that the two would have been taking a huge the risk that their early morning flight would be delayed, which would have kept them from making their Boston connection. Had this happened, the entire operation could have been compromised.

The second video, not released until 2004, is of much lower quality. It purports to show the five alleged hijackers of Flight 77 – Hani Hanjour, Nawaf al-Hazmi, Salem al-Hazmi, Khalid al-Mihdhar, and Majed Moqed – passing through a security checkpoint prior to boarding Flight 77 at Washington’s Dulles International Airport.

But unlike all other video from Dulles surveillance cameras, this does not feature any camera identification number (which would establish where the video was shot) or any time stamp. It is therefore impossible to establish where or when this video was shot, which means it is useless as evidence of whether these five boarded Flight 77.

On top of this, two of the alleged hijackers who were shown in the dubious video and who were supposed to have boarded Flight 77, Salem al-Hazmi and Khalid al-Midhhar, turned up alive after 9/11. Also damning is that at one point the video (as it was aired on CBS and Court TV) zooms in on al-Mihdhar and pans with him, which suggests human intervention that would not be found on any other airport surveillance video.[5]

No positive ID of remains: Apart from how hard it is to believe that identifiable remains of alleged hijackers could even have existed (we’re told most Flight 77 passengers remains were identified, while the cockpit voice recorder was destroyed because of the extreme temperatures), the fact is that there is no verifiable evidence that any physical remains of any alleged hijackers were recovered.

According to Davidsson, the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology used DNA to identify all the “innocent” passengers and crew members from the flights.[6] But none of the alleged hijackers’ identities were confirmed using DNA testing (no efforts were made to contact any of the families of the suspects to obtain DNA samples). Instead, a process of elimination was used with unidentified remains assumed to be those of hijackers.

Also, death certificates were issued for all passengers and crew of the four flights but none for the alleged hijackers. According to the FBI this is because they could not be sure of their identities. But in several cases, DNA samples could have been collected for comparison to the supposed remains. The family of Ziah Jarrah (alleged hijacker on Flight 93) even volunteered to co-operate with authorities, but this was declined.

Anomalies and mysteries for each flight

Let’s look at how some names were removed and replaced by others on the four flights and how at least 10 of the 19 men were still alive after 9/11:

Flight 11: Jay Kolar points to a very serious problem concerning the official story of the Flight 11 hijacker list: “A little-known fact is that besides the name of Mohamed Atta, it contained four names from the Flight 11 manifest, which the FBI dropped and replaced with four other Arab names. Are we then to believe there were at least nine Arab names on Flight 11 to choose from, and four of the FBI’s five choices were wrong?”

Mohamed Atta: ringleader?

The original list for Flight 11 included Atta, Adnan Bukhari, Ameer Bukhari, Abdul al-Omari, and Amer Kamfar. On Sept. 14, 2001, federal sources told CNN that Adnan and Ameer Bukhari had been on one of the planes that originated in Boston. Later, this was changed, and they became the pilots of the two planes that were reported to have hit the World Trade Center. Finally this was narrowed down to Flight 11.[7] We were also told that Adnan and Ameer had driven a rented car from Boston to Portland, Maine on Sept. 10, 2001. But that story had to be changed when CNN later reported that Adnan Bukhari was quite alive and still living in Florida, where he had been questioned by the FBI. And Ameer Bukhari had been killed in a small plane crash in Vero Beach, Florida on Sept. 11, 2000.

So these two names were dropped from the official “hijackers” list and replaced by two more: brothers Wail M. al-Shehri and Waleed M. al-Shehri. Both also turned up alive after 9/11. Waleed protested his innocence from Casablanca, Morocco. The BBC reported that Waleed al-Sheri had attended a flight training school in Daytona, Florida but had left the U.S. in 2000 for Saudi Arabia where he became a pilot with Saudi Arabian Airlines. Thierry Meyssan in his book 9/11: The Big Lie (p. 54) reported that al-Shehri had been interviewed by the Arab-language London-based newspaper Al-Qods al-Arabi after 9/11. Also, according to the Associated Press, he contacted the U.S. embassy in Morocco and explained that he lived in Casablanca and worked as a pilot.

On Sept. 12, 2001, eight FBI agents arrived at the door of Amer Kamfar’s neighbor in Vero Beach asking if the neighbor knew him. Later Kamfar’s name was removed from the list and replaced by Satam M.A. Al-Suqami (the alleged owner of the famous passport that we’re told floated to the ground near the towers after the first plane impact). But if Kamfar was on the original manifest, where did Al-Suqami’s name come from? And if Kamfar wasn’t on the original list, where did they get his name from?

And another name from the Flight 11 list was reported by the Boston Globe to be Abdulrahman al-Omari (who we were told sat next to Mohamed Atta on the plane). But on the list of hijackers released Sept. 14, 2001 by the Justice Department, the name was Abdulaziz al-Omari (sometimes written Abdul Aziz). Meanwhile, the Washington Post listed the name as Abdulrahman that same day. But Abdulaziz was living in Saudi Arabia, according to the Saudi embassy in Washington. The Independent reported on Sept. 17 that he had walked into the U.S. consulate in Jeddah to demand an explanation for why he was being accused of being a suicide hijacker.

Kolar’s research turned up some fascinating connections between the suspects whose names were on the initial list and then removed. In addition to all being Saudi Arabian pilots living in Vero Beach, Abdulrahman al-Omari and his family lived at the same address as Amer Kamfar. Next door lived Abdulaziz al-Omari. Ameer Bukhari was listed as having the same address as Adnan.[8]

It seems that every time there was a problem with an element of the official story, the story changed. This happened with the inexplicable trip by Mohamed Atta and Abdulaziz al-Omari to Portland, Maine mentioned above. Originally, the story was that it was the two Bukharis who had rented the car (a blue Nissan Altima) and driven to Portland. But when one turned out to be dead the year before and the other still alive, the story changed. Now it was Atta who had rented the car and driven with al-Omari to Portland. But it also came out that a white Mitsubishi rented by Atta was found at Logan Airport. Kolar notes the contradictions:

“When their destination was Boston, why would Atta and al-Omari rent one car in Boston and leave it at the Boston airport, then rent another car and leave it at the Portland, Maine airport, and take a flight back to Boston? The whole story makes no sense.” He adds that flying from Portland on 9/11 also makes no sense since the two risked missing their connecting flight in Boston. For more on the bizarre Portland trip, check David Ray Griffin’s article, “9/11 contradictions: Mohamed Atta’s Mitsubishi and his luggage.”

The original story reported in the media was that incriminating items, which helped cement the official story that the 19 men were working with al-Qaeda, were found in the car that Atta is supposed to have rented and that was found parked at Logan Airport. The items were said to include Atta’s will, an international driver’s license, instruction videos for flying Boeing airliners, an Islamic prayer schedule, and a Saudi passport. But this story later changed as well: the items were now found in Atta’s suitcase, which miraculously was the only one that did not make it on to the flight. Why would Atta bring his will with him on the plane if he was planning to crash it into a building?

To top things off, Atta’s father was quoted in The Guardian in September 2002 as saying that his son is still alive and in hiding from U.S. security services.

Flight 77: The first problem with the five alleged hijackers of Flight 77 is that Salem al-Hazmi turned up alive in Saudi Arabia, according to the Saudi embassy in Washington. He told reporter David Harrison of The Telegraph that he had just returned to a petrochemical complex in the city of Yanbu after a holiday when 9/11 occurred.

On Sept. 14, 2001, CNN had released the name of Mosear Caned, who they said was expected to be on a list of hijackers being released later that day. Instead, that name disappeared and was replaced by Hani Hanjour. But where did the first name come from? And if Hanjour purchased a ticket, then why wasn’t his name on the original list? On top of that, an ATM photo of Hanjour, taken six days before 9/11, does not resemble the Hanjour shown in the Dulles video.[9]

We know for a fact that the official (but unauthenticated ) passenger list from Flight 77 is not the same as the original one. We know that because the Counsel for American Airlines, in a 2004 letter to the 9/11 Commission, stated that they don’t know if Hanjour checked in at the main ticket counter. On Sept. 16, 2001, the Washington Post reported that Hanjour’s name was not on the original manifest because he may not have purchased a ticket. But his name appears on the list entered into evidence at the Zacarias Moussaoui trial.[10]

Also, the spelling of the names of the other four were changed slightly from the first list: Cammid Al-Madar became Khalid Al-Mihdhar; Majar Mokhed became Majed Moqed; Salem Al-Hazni became Salem Al-Hazmi; and Nawar Al-Hazni became Nawaf Al-Hazmi.

Flight 175: The list originally contained four names but a fifth, Mohand al-Sheri, was added later. But he turned up alive and living in Saudi Arabia, according to the Saudi embassy in Washington. Hamza al-Gamdi was supposed to have been a hijacker on Flight 175, but his family came forward to state that the photo released did not resemble him although the name and birth date matched.

Flight 93: Another who turned up alive was Saeed al-Ghamdi. He told David Harrison of The Telegraph that he was shocked to see his name on the list of hijackers and that he had spent the previous 10 months in Tunis learning to fly an Airbus. According to the BBC, al-Ghamdi had also been interviewed by the London-based Arab newspaper Asharq Al Awsat.

Another alleged hijacker, Ahmed al-Nami, told Harrison after 9/11 that he was shocked to see his name on the list of hijackers, adding that, “I had never even heard of Pennsylvania.” He stated that he had been working as an administrative supervisor for Saudi Arabian Airlines.

Photographic evidence shows that the Ziad Jarrah accused of being a hijacker is not the same person whose half burned photo was supposedly found at the “crash site” in Shanksville, PA. Kolar contends that Jarrah had a double as did several others accused of being part of the plot. He says there are accounts of Jarrah’s whereabouts that have him in more than one place at a time.

Kolar writes that investigators found that Jarrah had spent three months in an al-Qaeda training camp in January 2001. But according to Florida Flight Training Center, Jarrah was a student there until Jan. 15. Jarrah later went to Lebanon Jan. 26-30 to be with his father, who was having open-heart surgery.[11]

Lies within lies

Maybe the craziest pillar in the whole story comes from the so-called “confession” video of Osama bin Laden that was released in December 2001. The video is clearly a fake given that it features a bin Laden double, and not a very good one at that.[12]

But what’s really intriguing is that the fake bin Laden mentions the name of nine of the alleged hijackers during the confession. But five of those nine ended up still being alive. Why would the real perpetrator of the 9/11 crime give credit to five men who turned out not to be involved?

The story that 19 Muslims named by the FBI were responsible for hijacking four airliners and killing themselves in the process simply cannot stand up to examination. In fact we know for a fact that it is false.

This, like the rest of the official story of 9/11, is so thin you can see right through it.

Footnotes

[1] Kolar, page 3 of The Hidden History of 9-11.

[2] Kolar, page 40

[3] Davidsson, page 43 of Hijacking America’s Mind on 9/11: Counterfeiting Evidence

[4] Kolar, page 11

[5] Davidsson, page 54

[6] Kolar, page 7

[7] Kolar, page 3

[8] Kolar, page 13

[9] Kolar, page 8

[10] Davidsson, page 33

[11] More details on the framing of Ziad Jarrah, Kolar, page 301

[12] Kolar, page 9